Inflammation and regeneration

Tissues have a remarkable ability to repair themselves after injury, but this process depends on a delicate balance: cells must decide whether to die, temporarily pause their growth, or proliferate to regenerate the damaged area. These local decisions also need to be coordinated with systemic responses from other organs, such as those that provide nutrients to support regeneration. Our goal is to uncover the fundamental principles of the intra- and inter-organ signaling networks that restore tissue integrity and function after stress.

Our previous work has focused on how cells choose between division and death, guided by the well-conserved JNK/AP-1 and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. We also discovered that cells at the center of inflammatory wounds can temporarily acquire a senescence-like state characterized by cytokine release, resistance to cell death, and activation of protective pathways. While these adaptations help promote repair, their persistence under chronic inflammatory conditions can give rise to wound pathologies and even foster tumor development.

At present, we are investigating how senescent and regenerating cells in damaged tissues and tumors rewire their metabolism, epigenetic landscape, and cellular functions to support growth and repair. In parallel, we are expanding our focus to lipid metabolism across organs during inflammation, and to understanding whether ecologically relevant toxic compounds, such as pesticides, might interfere with tissue repair programs. A key open question is whether chronic activation of these repair networks under environmental stress contributes to the metabolic breakdown of inter-organ communication.

Tumor suppression and ‘Interface surveillance’

Epithelial tissues are constantly exposed to environmental challenges and therefore prone to mutations that give rise to aberrant cells. While the adaptive immune system in vertebrates contributes to their clearance, our research in the Drosophila invertebrate has uncovered powerful tissue-intrinsic surveillance mechanisms that eliminate abnormal cells before they can expand.

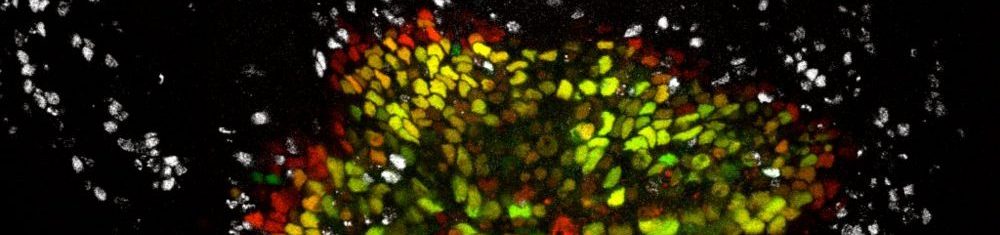

We have established a model in which aberrantly specified or oncogene-transformed cells (such as RasV12-expressing clones) are recognized and eliminated by their healthy neighbors through a process we call interface surveillance. This elimination is strictly contact-dependent: direct cell-cell interactions between normal and abnormal cells trigger signaling cascades that drive the removal of the aberrant cells.

Our recent work has identified key cell-surface receptors involved in this recognition. Robo family receptors, best known for axon guidance, and Toll-like receptors, classically associated with innate immunity, both act as surface markers of cell fate identity. A critical principle emerging from these studies is that recognition does not rely on the absolute presence or absence of a receptor, but on differences in expression levels of these surface markers between neighboring cells. These mismatches initiate stress signaling, including JNK activation, and ultimately trigger the extrusion or death of aberrant cells.

We are now dissecting the molecular logic of cell–cell recognition: how tissues “read out” relative differences in surface protein expression to decide whether a neighbor belongs or should be eliminated. Understanding this logic could reveal general design principles of tissue quality control and suggest new strategies to reinforce tumor-suppressive barriers.

Tissue morphogenesis

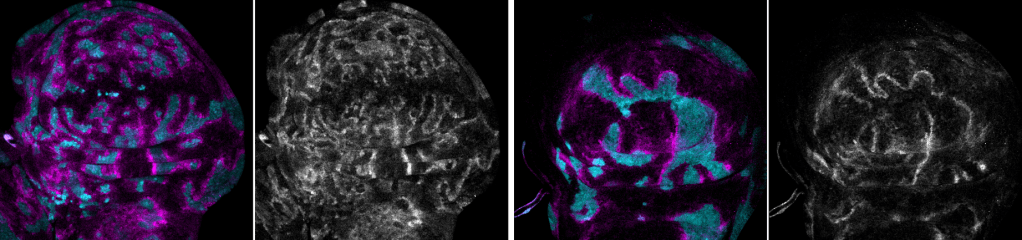

We study how cells and different cell lineages work together to shape biological structures during tissue morphogenesis. Currently, our focus is on the interaction between somatic and germline cells during the development of the Drosophila egg chamber (oogenesis).

In many species, oocytes develop within a germline cyst, which includes the oocyte itself, nurse cells that provide nutrients, and a surrounding somatic epithelium. Nurse cells undergo programmed cell death at the end of oogenesis, while somatic epithelial cells either support oocyte maturation or facilitate nurse cell removal. Coordinated morphogenesis between these different cell types is essential for managing the significant volume changes that occur during oocyte growth.

Our research has shown that the transcriptional regulator Eyes absent (Eya) plays a key role in establishing differential cell-cell affinity between somatic and germline cells. This process influences the redistribution of somatic cells across the germline surface, regulating oocyte growth and ensuring proper alignment between germline and somatic counterparts. This mechanism is essential for the self-organization of tissues during oogenesis and highlights the importance of differential affinity between cell lineages in assembling functional biological structures.

We are currently investigating the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate soma-germline affinity and maintain mechanical equilibrium in the egg chamber during different phases of oocyte growth. Our focus includes the role of transmembrane adhesion receptors in differential adhesion, the modulation of cortical tension via actomyosin networks, and the remodeling of cell protrusions such as lamellipodia and filopodia during soma-germline interactions.